The latest acquisition to my collection is the Universal Vitar, a 35mm full-frame camera that was produced by Universal in 1951. At this point the company was veering toward bankruptcy as a result of supplier problems, bad luck, and some really awful management decisions. You’ll have to read Cynthia Repinski’s book for the details of this debacle, as I can’t bring myself to repeat the story.

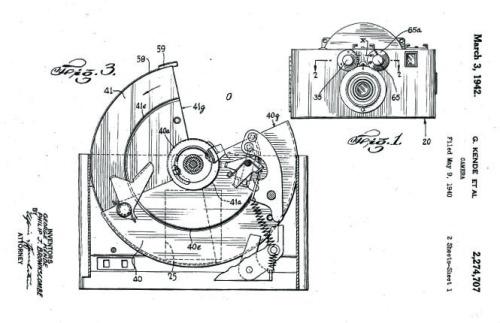

Suffice it to say that by 1951, the Universal Camera Company had debts that dated back to shortly after the war, having liquidated most of their finished goods at a near-loss, and still didn’t have the funds to buy materials to make new products. Their chief engineer and visionary, George Kende, had resigned in 1948. They needed a new line of cameras to sell, but they had practically no resources with which to make it happen.

What they did have in abundance were leftover parts from the production of previous camera models that hadn’t sold as expected. So it was decided to construct “new” models from the parts available in inventory. They designed three cameras from spare parts: a 35mm full-frame camera, a 2-1/4 x 2-1/4 TLR, and an 8mm cine camera.

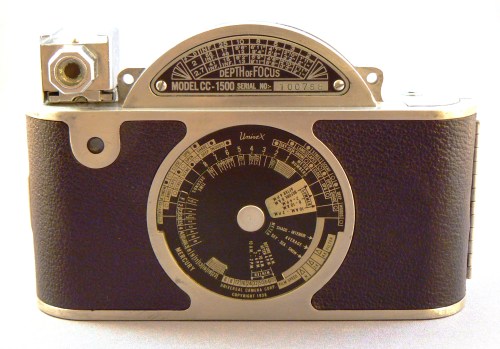

The 35mm camera that resulted was the Vitar. It was made from the Bakelite body of the Buccaneer, the viewfinder/extinction meter and hot shoe from the Meteor, the shutter from the Uniflex I, and a 50mm f/3.5 Tricor lens that appears to be the Buccaneer lens mounted on the Uniflex shutter, possibly with parts from the Roamer. The nameplates are all new, but apart from that the camera is entirely constructed from parts on hand.

The Roamer may have contributed lens elements or mounting rings, but not the shutter as stated by Repinski

The Vitar definitely looks like a camera built from spare parts. It has a shutter that not coupled to the film wind mechanism in any way. Thus, there is no double exposure prevention. The shutter release is mounted on the lens/shutter assembly rather than on the camera body. The lack of a body-mounted shutter release is a glaring omission for a camera made as late as 1951. Not only is this odd for a camera of the time, but it’s especially odd for a camera produced by this company: both the Corsair and Buccaneer had body-mounted releases, and their design was patented. Apparently, there were no parts available to build the more sophisticated body-mounted release, so the hole in the camera body where the release button was intended to go was simply plugged with a chunk of aluminum.

Another sign of slapdash construction becomes apparent with removal of the front lens assembly, revealing that the unit is shimmed in place using an old nameplate from the lens of a Roamer (or maybe a Uniflex).

And yet, despite it all, the camera actually performed quite well. I corresponded with Sam Sherman, a fellow collector, back in 2000 on the subject of Unversal cameras, and it turned out that he had owned a Vitar at the age of 11. He wrote:

“I sold my first commercial photos to Dance Magazine at the age of 11, which I shot with a Universal Vitar, a fine camera and far superior to the more famous Argus A series and others. “

Sam, who was a producer and distributor of films in Hollywood for many years, had at that time about 15 Universal items in his collection. And he’s right about the quality of the lens compared to the Argus A. Universal had their own optical shop, and they invented most of the lens grinding equipment used in their own production – the same equipment they used to produce binoculars during the war. Argus was said to buy their lens elements in bulk, and the Argus A’s were famous for producing fuzzy negatives.

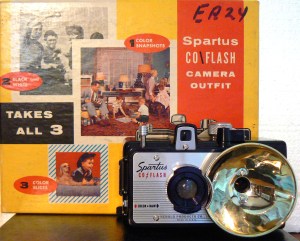

I got this camera from another fellow collector, Wayne Cogan. Wayne gave me the Vitar in trade for a couple of cameras that I suspect he really didn’t need, simply because he wanted me to have it for my collection. It’s a rare item, especially since it came in its original box with instructions. I’m hoping to get the camera refurbished to the extent that it can be used to take a few shots – I’d really like to evaluate its performance for myself. But the shutter is not working at the moment, and neither is the film wind mechanism, so I’ll need some help with the details. Anyone out there know anything about the 4-speed Synchromatic shutter?

Anyhow, thanks to Sam and Wayne for encouragement and help. Merry Christmas to all you camera collectors out there, and may the New Year bring you new additions to your collections!